Chapter 6: Algorithms

Learning Objectives

- Learn about nested control structures.

- Be introduced to techniques for solving problems with algorithms.

- Learn about pseudocode and flowcharts.

- See more examples of problems and algorithms.

6.1 Overview

In the last couple of chapters we looked at if and else statements, and looping. These statements are examples of control flow statements, because they control the flow of the program — that is they change the order the other statements run in.

In this chapter we will look at some more examples of these control flow statements, and learn some new things we can do with them. In particular, we will talk about nesting if and else statements and loops together. Doing this will allow us to write more complex problems and solve some problems we couldn’t otherwise solve.

With these tools, we can also start to tackle some more interesting problems. So this chapter will also talk about some techniques for solving problems. Lastly we will look at a handful of example problems, and talk about how we can go about breaking them down before giving code to solve them.

6.2 Nesting Control Statements

So far our programs have only used an if and else statement, or a loop at one time. But to make more complex programs, we can start to combine them up together. We can do that by nesting them together. For example, we can put an if/else statement inside of a loop. Or a loop inside of an if statement. Or even a loop inside of another loop.

As a first example, let’s look at a program to read numbers from the user and tell the user if each number is even or odd. The user would be able to enter as many numbers as they want, and enter 0 to quit.

To do this, we will need a while loop to keep reading in the numbers. We will also need an if/else statement to check if the number is even or not. The if/else can’t be after the loop, because it needs to check every single number read in. Instead it has to be inside the loop.

The code for doing this is below:

# read the first number

num = int(input("Enter a number: "))

# keep going while it's not 0

while num != 0:

# do the even/odd check

if num % 2 == 0:

print("Even")

else:

print("Odd")

# get the next number

num = int(input("Enter next number: "))The % operator is new, so we need to explain that first.

What this does is checks the remainder of a division. For instance if we

divide 13 by 5, we get 2 with a remainder of 3. So 13 % 5

is equal to 3. If the remainder when dividing by 2 is 0, it

means there is no remainder, so the number is even.

Here the if/else is nested inside of the loop. Every time the loop is done, we check the if condition and do either the if part or the else part. Remember that the indentation is what tells us what part of the code is part of the loop. Since the if and else statements are indented, they are part of the loop. That’s what nesting means in computer science — that something is part of something else.

There is no restriction on nesting like this. We could instead put a loop inside of an if statement, or a loop inside of another loop. We could even put a loop inside of an if statement which is part of another loop. We will see more examples of nested control structures as we go along.

6.3 Example: Guess the Number

Now that we know how to nest if statements with loops, we can finally tackle a Python version of the “Guess the Number” algorithm we looked at way back in Chapter 1. The algorithm is given again in pseudocode:

1. Set min to 1.

2. Set max to 100.

3. Set G to (max + min) ÷ 2 (rounding down if needed).

4. Ask if their number is G.

5. If it is, then we are done!

6. If the guess was too high, set max to (G - 1).

7. If the guess was too low, set min to (G + 1).

8. Go back to step 3.Notice that we have a loop (steps 3 through 8) with an if/elif/else statement inside of it (steps 5 through 7). So our program will need to nest these statements too.

The Python code to solve this problem is below:

# set initial values for our variables

min = 1

max = 100

done = False

while not done:

# ask them if this is their number or not

G = int((max + min) / 2)

answer = input("Is your number " + str(G) + "? ")

# respond to their answer

if answer == "yes":

done = True

elif answer == "too low":

min = G + 1

elif answer == "too high":

max = G - 1

else:

print("Answers are 'yes', 'too low', or 'too high'.")

# when we exit the loop, we have guessed the number

print("Got it!")There are some things to point out about this program. First, we are

using a boolean variable, called done to keep track of

whether or not to exit the loop. The variable starts off as False, and

we set it to True when we find the user’s number. Because our condition

tells us to keep looping while we are not done, the loop will keep going

until we guess right.

Another thing to point out is that we solve the problem of rounding

down by calling the int function. We have used this

function to change a string (like “12”) into an integer (like 12). It

can also be used to change a float number (like 12.5) into an integer

(like 12). The round function could be used to round to the

nearest whole number, but not to always round down like we want

here.

We are also calling the str function to convert the

variable G into a string. The reason for this is that input

doesn’t allow us to pass multiple things to be printed like

print does. We have to pass 1 string. We do this by joining

the different parts of our questions, but we can only join strings with

the + operator — not integers. So we use str to convert

from a number (like 12) into a string (like “12”).

And crucially the if statement chain for testing if we got our guess right or not is nested inside the while loop. You can tell this because it is indented over. We need to do this because we need to do the test for every guess we make, not just one.

Here is an example run of this program:

Is your number 50? too high

Is your number 25? too low

Is your number 37? too high

Is your number 31? too low

Is your number 34? yes

Got it!6.4 Example: Password Strength

Let’s look at another example now. Many websites require user passwords to meet certain standards. For example, our university has the following requirements for passwords:

- Be at least 8 characters long

- Include at least one upper-case letter

- Include at least one lower-case letter

- Include at least one digit

We already know how to check if the string is long enough with the

len function. The other ones are a bit trickier though. The

approach we will take is to loop through the entire password one

character at a time. For each character, we will check if it is one of

the three things we need to look for.

In order to do this, we will need a couple new string methods. These

are isupper, islower, and

isdigit. These each return true if the string contains only

upper-case letters, lower-case letters or digits respectively. We’ll

call these on each letter to see what sort of character it is.

In doing this, we also need to keep track of whether any of

the symbols in the password are in one of these three categories or not.

We will do this by having a boolean variable for each category. For

instance, we can have a variable called upper which starts

at false. Then, when we see an upper-case character, we will set it to

true.

The code for solving this problem is given below:

# read the password from the user

password = input("Enter password: ")

# check the length first

if len(password) < 8:

print("Password must be 8 characters or more.")

else:

# length OK, now check contents

upper = False

lower = False

digit = False

# check each chatacter to see if it's in these categories

for char in password:

if char.isupper():

upper = True

elif char.islower():

lower = True

elif char.isdigit():

digit = True

# now check if all three categories are met or not

if not upper:

print("Password must contain an upper-case letter.")

elif not lower:

print("Password must contain a lower-case letter.")

elif not digit:

print("Password must contain a digit.")

else:

print("Password is accepted!")This is the longest program we have seen so far! It also has a few nested statements, so let’s go through it carefully so we can be sure to understand it. The program starts by reading in your password. Next it does the check to see if it is at least 8 characters. If not, it gives you a message saying it’s not long enough.

The rest of the program is in the else statement. That

means the rest of the checks only happen when the password is

long enough. We start by making one variable for each category we have

to check, and setting them all to false. We will assume we don’t have

any of these until we see one.

Next, we loop through every character in the string with a for loop. For each character, we check if it’s a upper-case letter, lower-case letter or digit. In each case we set the corresponding variable to true.

When we are done going through the loop, we will have checked every single character in the password. If any of our three boolean variables is still false, that means that type of thing must not have been present in the password.

We then finish up by checking those three variables in an if/elif/else statement. If any one of them was false, we scold the user saying their password needed one of those characters. In the else clause, we know that their password met all the criteria, so we declare that it is accepted.

6.5 Example: Times Tables

Now we will look at an example of nested loops. That would be one loop nested inside of another loop. An example of a problem we could solve with nested loops is the problem of printing out a times table. A times table is a table which shows what one number multiplied by another is. You probably had to memorize this table in grade school.

Let’s say we want to print a 10 by 10 times table like the following:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20

3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30

4 8 12 16 20 24 28 32 36 40

5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50

6 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 54 60

7 14 21 28 35 42 49 56 63 70

8 16 24 32 40 48 56 64 72 80

9 18 27 36 45 54 63 72 81 90

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 To do this, we will need two nested loops. The first loop will loop through each of the ten rows of the table. Then the inner loop will go through each of the ten columns of the table. Then in that loop we print one number. The basic algorithm would look like this:

for each row:

for each column:

print this row number times this column numberBecause the column loop is nested inside the row loop, it will be done in its entirety for every row. With ten rows and ten columns, we will get a total of 100 numbers printed out.

The Python code for this program is below:

# read the size of the table

size = int(input("What size table would you like? "))

# loop through each row

for row in range(1, size + 1):

# loop through each column

for col in range(1, size + 1):

# print one 'cell' of the table

print(row * col, end="\t")

# go to the next line after this row is done

print()There are a couple things to notice here. First, we have our nested

loops. Each loop goes through the numbers 1 to 10. We also have to give

them a different variable (row and col in this

case). We couldn’t use “i” for both because then one would overwrite the

other.

Also we pass size + 1 as the end point to the

range function. That allows us to loop more or less

depending on how big of a table the user requested.

The print that outputs the number uses the two variables

row and col multiplied together. We don’t want

each number to be on a line all by itself, so we have to tell Python not

to end with a new line. Instead we pass end="\t". The

"\t" is a tab character. By putting a tab after

each character, we make sure the numbers line up nicely in columns. We

could have used a space and it would have worked, just looked a little

messier.

Then we have the funky looking line that calls print()

with nothing at all between the parenthesis. The purpose of this is to

go down to the next line. Each time we print a number, we end with a

tab. Then after one row is done (after the inner for loop has finished),

we need to go down to the next line so the next row has room. That’s

what that second print accomplishes.

Nested loops can be tricky because you have to keep track of where you are in both at the same time.

6.6 Breaking Down Problems

As we mentioned in Chapter 1, computer science is not really the study of computers — it is the study of algorithms. The main thing that computer scientists do is come up with algorithms to solve various problems. Usually they write the algorithms in a programming language like Python, but coming up with the algorithm in the first place is usually the hard part.

Like any intellectual skill, learning to develop algorithms is something that takes a bunch of time and practice. That said, there are some techniques for breaking down a problem so that you can go about solving it. This section will give some advice for doing this.

The following are steps that I think are good to go through when tackling a new problem:

Identify the inputs

Most problems have some kind of information which is given to you as input. Your algorithm is generally going to have to use this input in some way, so listing out what inputs you will need is a good starting point.

Identify the outputs

For most problems, there is also some kind of solution that you are looking for. If we don’t have the output we are looking for firmly in mind, it will be hard to hit upon the right algorithm. Listing the outputs our algorithm is expected to produce will make sure we know our goal.

Solve a few examples by hand

Next you should solve a few examples of the problem just by hand. If you can’t solve the problem with example inputs, then you have no hope of coming up with an algorithm that can solve it in general. When doing this, it’s good to try examples of the different situations that could arise.

By working through a few concrete examples, you are doing two things. First you are making sure that you really understand the problem before diving into an algorithm. Secondly, you are going through the steps that your algorithm will need to go through which will give you insight into writing it.

Write the basic steps

Based on what you learned working the example problems, you can now sketch out the algorithm. But rather than jump right into Python code, it’s often helpful to start with righting down the basic steps in English first.

The main reason for this is because it’s easier to focus on just the algorithm and not the details of a programming language. For example, you don’t need to worry about deciding whether things should be int or float, or making sure parenthesis line up right.

This English like description of an algorithm is sometimes called “pseudocode” because it is sort of like computer code, but not really in any actual language. The main benefit of this is that it lets us focus on the algorithm without being distracted by details of Python syntax.

Test the steps

Another benefit of using pseudocode is that we can now test out the algorithm in its simple English-like steps before coding it. We should follow the steps a couple of times to make sure that it gets the right answers. If we made any mistakes, or if it is wrong in some cases, we can fix it before we spend the time making it a program. Algorithms in pseudocode can be easier to fix than programs in a full programming language.

Write the actual code

Once we are confident our basic algorithm is working, we can start putting it into actual code in a programming language (we’ll use Python of course). Now instead of focusing on the problem itself, we will focus on the language’s syntax and finding all the functions we need.

Test the code

Now we can test our code out to see if it gives us the answers that we expect. We should be able to plug in the inputs for the examples we solved by hand and get the right answers.

Another benefit of splitting our problem-solving steps into two parts is that we should not have to fix problems with the actual algorithm any more (those should have been caught in step 5). Any problems now should be with translating our pseudocode steps into actual Python code.

Experienced programmers will often skip steps 4 and 5, and jump right into writing code when they have an idea of how to solve a problem. The main reason for this is that they are so comfortable with the programming language they are using. An experienced programmer can translate steps into code as they go. For a beginner this is harder. And even experienced programmers will often fall back to writing the steps in English first when they run into an especially tricky problem1.

6.7 Breaking Down Problems Example

As an example of applying these steps, let’s solve the problem of figuring out how much somebody is paid given their hourly rate and the number of hours they worked. If the hours worked are over 40, then the person is paid “time and a half” for their overtime.

It’s worth pointing out that the problem of solving one specific case of this problem (like if you worked 30 hours and make 12 dollars per hour) is just a math problem. It becomes a computer science problem when we want to solve it in general. With the right algorithm, we could solve any case of this problem at all — no matter what the inputs are, our algorithm will give us the right answer.

Let’s go through the steps outlined above:

Identify the inputs

For this problem we have two pieces of input: the hourly rate and the number of hours worked.

Identify the outputs

In this case, we only want one output, which is the amount of money earned.

Solve a few examples by hand

For this problem, we should solve an example where the person doesn’t get overtime and one where they do. Let’s start with the case where they don’t get overtime. Say they work for 30 hours, and make 12 dollars per hour. In this case, we should just multiply the two numbers together to get 30×12 = 360.

In the case where the employee does get overtime, we have to do something extra. Let’s say they work 45 hours and make 10 dollars per hour. Now we need to give them 10 dollars for each of the 40 regular hours they are working. We also need to pay them extra for the hours they work over 40. In this case that’s 5 hours at 15 dollars per hour. So in total we have 40×10 + 5×15 = 475.

Write the basic steps

We should use the steps we took solving the problem above to guide us in writing them out in pseudocode. We will have identified the two main cases in this problem, and might come up with something as straightforward as the following:

1. Read in the hours 2. Read in the wage 3. If they worked 40 hours or less, pay will be (hours * wage) 4. Otherwise, pay will be: 40 * wage + (hours - 40) * (wage * 1.5) 5. Print out the payTest the steps

In this case, we can run through these steps with a couple of example inputs to make sure they work. We can even use the ones we worked through by hand to make sure they get the same answer we arrived at.

If something does go wrong here, we should modify the algorithm at this point before moving on.

Write the actual code

Now that we have an algorithm that we are pretty confident with, we can go through and translate it into Python code. In this case, we can write something like this:

hours = float(input("How many hours did you work? ")) wage = float(input("What is your hourly wage? ")) if hours <= 40: pay = hours * wage else: pay = 40 * wage + (hours - 40) * (wage * 1.5) print("Your pay will be", pay)Test the code

Finally we can test this code to make sure the results it gives matches what we expect. We should be able to run this code and give it the inputs we tested in step 3 to make sure it gets the same result that we got.

Because this problem isn’t terribly difficult, many of you could probably have jumped straight into code. The point of this section is to give an example of solving problems this way. These steps will be helpful to at least think about when you encounter trickier problems.

6.8 Flowcharts

Another tool that computer scientists use to solve problems before jumping into code is the flowchart. A flowchart shows the steps of an algorithm, just like pseudocode does. A flowchart however makes the decisions in the algorithm really clear by having arrows that show what steps happen when.

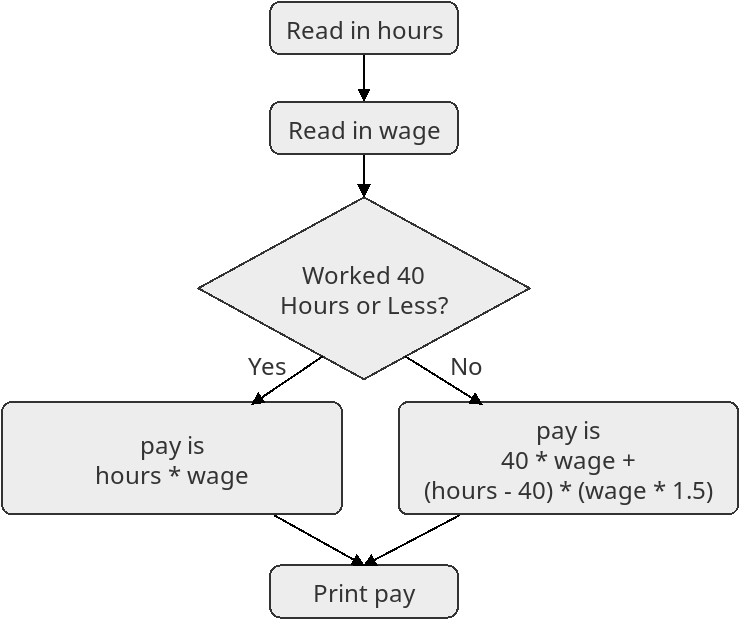

Below is an example of a flowchart for the overtime program:

The flowchart shows the algorithm in a slightly more graphical way. Each box in the chart displays one step of the algorithm. The nice thing about a flowchart is that it makes the control flow statements really clear. In this case, you can see the decision (which is typically shown with a diamond shape in a flowchart), with branches for the “yes” and “no” cases.

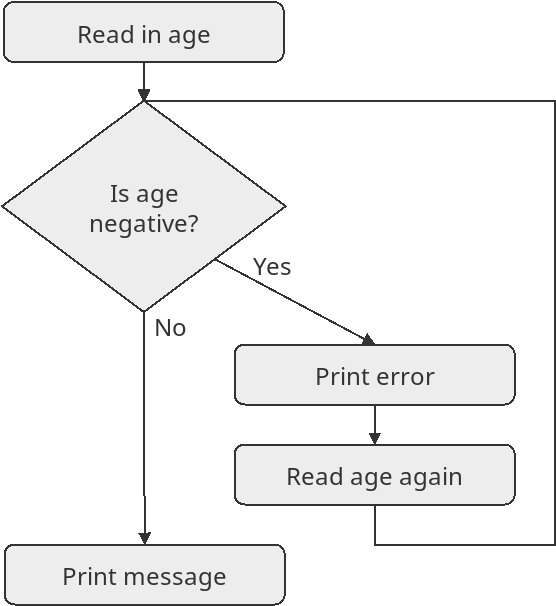

Flowcharts also make loops easy to spot. We can make a flowchart for the problem of reading a valid age from the user. The steps in the following algorithm keep asking the user for an age until they put in something that’s not negative:

You can see the loop in this algorithm because of the arrow that’s pointing back to a previous step (that’s the arrow pointing from the “Read age again” step back around to the decision). Making flowcharts can be helpful as you are working on an algorithm, as they can help you understand the order that the steps need to be done in.

6.9 Comprehension Questions

- Explain what is meant by “nesting” control structures such as if statements and loops.

- How can you determine whether a line of code is part of a loop, or comes after the loop?

- If we have a loop that executes 10 times, then nested within that is a loop that executes 3 times, how many times does a print statement within the inner loop execute?

- What is pseudocode and how does it aid in developing algorithms?

- How do flowcharts help in understanding and solving programming problems?

- Why is testing each step of an algorithm important before implementing it in code?

6.10 Programming Exercises

Write a program which counts how many times a character appears within a string. Begin by reading in a string from the user. Next, read in a single character (which is just a string you can assume has length 1). Loop over the string and count how many characters match the one you are looking for, and report that to the user at the end.

It’s harder than you probably think to determine if a year is a leap year or not – it’s not just every 4 years. The rules are:

1. If the year is divisible by 400 it’s a leap year 2. Else if it’s divisible by 100 it’s not a leap year 3. Else if it’s divisible by 4 it is a leap year 4. Otherwise it’s not a leap yearWrite a Python program to read in a year and tell the user whether it’s a leap year or not.

Write a program to find the largest number in a sequence. Start by asking the user to tell you how many numbers they will provide. Next write a loop that runs that many times. Inside the loop, ask the user to give you a number and keep track of which one is the biggest. At the end of the program, you should print the largest number in the sequence the user entered.

The Collatz Conjecture states that if we take any integer N , and repeatedly do the following steps to it:

If it’s even, divide it by two If it’s odd, multiply it by 3 and add 1.Then we will eventually hit 1. For example if we start with 5, we go though the following steps:

5 (starting number) 16 (times by 3 and add 1) 8 (divide by 2) 4 (divide by 2) 2 (divide by 2) 1 (divide by 2)This conjecture was raised by mathematician Lothar Collatz in 1937. Every number anyone has ever tried has eventually gotten to 1, but mathematicians have not been able to prove if this will work for all numbers or not.

You should write a program which reads in the starting number and prints out the numbers in the sequence until you hit 1.

An infinite series is a list of numbers with some repeating pattern to them. One famous infinite series is the following: \(\frac{1}{1} + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{8} + \frac{1}{16} + \frac{1}{32} + \frac{1}{64}\) Write a program to read in a number, called N, from the user. Then add up the first N numbers in this series. For example, if the user enters 3, it should add \(\frac{1}{1} + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4}\) and print the answer.

Chapter Summary

- If, elif and else statements, along with our loop statements form Python’s “control flow” statements. These allow us to control the order that program instructions are done in.

- These control flow statements can be combined, or nested, any way we like. We can put a loop inside of an if statement, or an if statement inside of a loop for example. This ability allows us to solve more complex problems.

- When tackling a new problem, there are some steps to go about

solving the problem:

- Identify the inputs

- Identify the outputs

- Solve a few examples by hand

- Write the steps needed in plain English

- Test these steps and look for problems with them

- Translate your algorithm into code

- Test the code you’ve written

- You can use pseudocode or flowcharts to work on the general solution to a problem before diving into code.

- To get better at algorithmic problem solving, you need to practice solving problems!

Footnotes

When I personally am writing programs, I will often start by writing my “basic steps” as comments in my program files. Then I read through and make sure the steps make sense before jumping into the code. Then, I add the code, but leave the comments in to explain how the code is working. I find this method works well.↩︎