Chapter 3: Types and Operations

Learning Objectives

- Understand the idea of type.

- Learn about the Python string type, and some of its operations.

- Learn about the two number types in Python: integers and floats.

- See how to get numbers as input from the user.

- Understand how to perform math operations on number in Python.

3.1 What are Types?

Just like us, programs need to keep track of information as they are solving problems or making decisions. They do this by storing data inside of variables. Last chapter, we saw how to create variables and also how to read input from the user and store it in variables. We didn’t talk about this, but we did it using one type of data, called the string type.

Python actually provides multiple types of data. A type is something associated with a variable that determines what sorts of things you can do with it. To be able to use a variable, you need to know what type it has.

For example, you probably have a first name like “Anne”, and a last name, like “Smith”. In Python, these are called strings. You can do some things with strings like join them together, to get “Anne Smith”. Or see how many letters they have. Other things don’t make sense to do with strings. For example, you can’t subtract strings — that just doesn’t make any sense.

You also have a birth year, like 1998. You can do different things with that piece of information. For example, you can subtract it from other numbers. We can subtract 1998 from the current year to see how old you are.

Python has several different types for dealing with different kinds of information like this. In this chapter, we will look at strings and numbers. We will also talk about some of the operations we can do with these.

3.2 Strings

The first type that we will look into is the string type. A string is some text inside of a program. For instance a message, name, address, email, password, URL etc. are all textual and would be stored as strings in a Python program.

Strings can be created by enclosing text inside of double quotes:

name = "Anne Smith"

print(name)Strings can also be enclosed inside of single quotes instead:

name = 'Anne Smith'

print(name)There is usually no difference between the two ways of making strings. The exception is when a string contains a quote. For example, this program is just not going to work:

answer = input("Answer "yes" or "no" here ")

print(answer)The problem here (which you can see from the way the code is

highlighted) is that when Python sees the " at the start of

"yes", it thinks that the string is over. Then it gets

really confused because it can’t figure out what to do with the yes. To

fix this, we can use single quotes instead:

answer = input('Answer "yes" or "no" here ')

print(answer)Now this is OK because Python knows that the string is not over until

it sees the second ' symbol. This goes the other way too.

For example this program has an error:

print('You can't enter a negative number!')But this one is fine:

print("You can't enter a negative number!")Personally, I always use the double-quotes unless the string I am writing needs to have double-quotes in it.

3.3 Joining Strings

Next we will talk about some of the operations that you can do with strings. The first one we will talk about is joining strings, which is also sometimes called concatenating1.

This is done by putting two existing strings together with a + in between them. For example, the following program asks the user for their first and last name, and then joins them together to form a full name:

# read the names from the user

first = input("What is your first name? ")

last = input("What is your last name? ")

# join them together in a new variable

fullName = first + last

print(fullName)Below is an example of this program being run:

What is your first name? Anne

What is your last name? Smith

AnneSmithThis program has three variables, which are all strings. The first contains the input the user gave for the first name (“Anne” in this example), the second contains the last name (“Smith”), and the third is created by joining the two names (“AnneSmith”), which is then printed out.

We can add as many strings together as we want. For example, we can make it so there is a space between the users first and last name by joining a space in between them. The program with this fix is here:

Program 3.1

# read the names from the user

first = input("What is your first name? ")

last = input("What is your last name? ")

# join them together in a new variable, with a space

fullName = first + " " + last

print(fullName)3.4 String Length and Indexing

A string is a sequence of one or more characters. A

character is just a single symbol of text, such as a letter, numeral,

punctuation or space. For instance, the string string

"Hello World!" has 12 characters: 10 letters, a space, and

an exclamation mark.

We can get the length of a string by using the len

function. The following program will get a string from the user and then

print how long it is:

Program 3.2

# program to print the length of the user's input

response = input("Enter a string: ")

length = len(response)

print("That string has", length, "characters.")Below is an example run of this program:

Enter a string: Hello out there!!

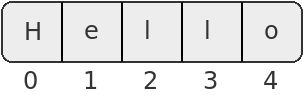

That string has 17 characters.We can also get any individual characters out of a string if we want to. Each character in a string has an index. The index starts at 0 and goes up by 1 for each character. For instance, the string “Hello” has these indices:

Notice that, while there are 5 letters, the indices go from 0 to 4, and that 5 is not the index of any letter. To get just one character from a string, we put the name of the string, then the index we want inside of square brackets.

For example, we can write a program that prints out the first letter of our input like this:

Program 3.3

# program to print just the first letter of the user's input

response = input("Enter a string: ")

first = response[0]

print(first)Here is an example of this program running:

Enter a string: Hello out there!!

HThis may not seem terribly useful, but getting the characters out of a string is sometimes necessary. For example, if a string has several things in it, like a first name and a last name, you may need to look at each character to see where the first name ends and the last name begins.

3.5 String Methods

There are other things we can do with strings, but first we need to

talk about a new term. We have seen several functions print

and input which are called functions. There is a

similar concept in Python called a method which is like

a function, but is called on a variable. To call a method, you give the

variable, then a . then the name of the method, and finally

parenthesis.

For instance, strings have a method called upper which

gives back a version of the string in all capital letters. We can call

this method like this:

mesg = input("Enter a message: ")

allcaps = mesg.upper()

print(allcaps)Here we get a string from the user with input. Then we

call the upper method on that string. This gives us back a

new string with all the lower-case letters swapped for capital ones. We

then print that out. Here’s an example run:

Enter a message: hello there.

HELLO THERE.There is also a method called lower which gives us the

all lower-case version. There are a few more helpful methods that we

will see in examples later in this book. The important thing to take

note of here is that these methods only make sense on strings. Numbers,

or other types of data can’t be lower-case or upper-case. So the type of

thing you have is important.

3.6 Numbers

Many programs work with numerical data, so numbers are another important type in Python. As we will see, numbers come up a lot more in programming than you might think. Even things like games need lots of numbers to work. For example, the positions of everything on the screen are stored as numbers.

Python actually has a few different types of numbers for different situations.

The first is the integer, or int type. Integers are

numbers that have no fractional component. For example, an int can be

equal to 3, or 4, but not 3.5. Integers can be positive or negative.

Some languages have limits on how big an integer can be, but Python

allows integers to be as big as they need to be2.

We can create an integer just by putting a number into a program. We can also assign it to a variable to keep track of it. For example, to create a variable to keep track of the year someone was born, we could do so like this:

birthYear = 1998Integers cannot have any fractional component. So if we make a number

that does have a fraction in it, Python gives it a different type,

called a float3:

size = 10.2A float is a number which can have a fractional part. That fractional part might be 0 though. For example, if you make a variable equal to 3.0, then it will be stored as a float, which just happens to have the fractional part equal to 0.

You may wonder why not just have all numbers be floats, since they can have fractional parts, but also can be set to numbers without a fractional part. The reason is that floats don’t store numbers exactly; they only store approximations of them. The reason for this is that some numbers, like Pi, would require infinite memory to store exactly.

We can see this effect by giving Python certain computations like the following (the >>> indicates that line is typed into the shell window):

>>> 0.1 + 0.2

0.30000000000000004Of course the answer should really be 0.3, but Python gives us a number that is almost, but not exactly, 0.3. This might seem like a flaw in Python, but it just comes from the fact that there are infinitely many real numbers between 0 and 1 — we can’t store them all perfectly in a computer. That’s just life. The small amount of imprecision we get with floats is normally not an issue.

As a rule of thumb, you should use integers when a number won’t have a fractional component, because integers are exact. When a number might have a fraction, you have to use a float.

3.7 Number Input

To read in a float from the user, we can’t just use the

input function. This always gives us a string, even if the

user types in a number. You can see this in the following shell example,

where we read in a variable and then check its type. The

type function returns the type of what you give it:

>>> num = input("Enter a number ")

Enter a number 7

>>> type(num)

<class 'str'>This is probably confusing, because 7 obviously is a number.

But strings can contain digits too. For instance, if you are reading in

an address, it might be something like

"1301 College Avenue". So strings can contain numbers

inside of them. This one just happens to contain only a number. Python

doesn’t automatically set the type based on what the user types in.

Now because it’s a string, we can’t really use it like a number. For example, if we try to add this variable to another number, we will get an error.

In order to actually get a number from the user, we need to convert

it into either an int or float first. This can be done by putting either

int() or float() around the input line, like

this:

num1 = int(input("Enter an integer "))

num2 = float(input("Enter a float "))The first example will read in the user’s input and convert it to an integer. The second will convert it into a float. If the user puts in something that is not correct, the program will stop with an error. For example, if we put in “3.5” for the first line, or “banana” for either line, the program won’t continue.

We’ll learn how to catch these sorts of errors and handle them later on.

3.8 Doing Math

Once we have numbers inside a Python program, there are lots of things we can do with them. We saw that + can be used to join together strings. With numbers it adds them together. The following program reads two float numbers from the user and then adds them together, displaying the result:

Program 3.4

# this program adds two numbers given by the user

num1 = float(input("Enter a number: "))

num2 = float(input("Enter a number: "))

total = num1 + num2

print("The total is", total)This program reads in the two numbers from the user, and stores them

in variables called num1 and num2. It then

adds them together using the + operation. Because these are numbers,

this results in getting the sum of the two. This is why types are

important — if they were strings it would have joined them. The result

of the addition is stored in the variable called “total” which is then

printed to the screen.

Of course Python has other operations besides just addition. Below is a list of some operators that Python supports:

| Operator | Meaning |

|---|---|

| + | Addition |

| - | Subtraction |

| * | Multiplication |

| / | Division |

| ** | Exponentiation |

Using the + and - symbols for addition and subtraction is probably pretty familiar to you. Some of the others might take a little while to get used to.

Programming languages were made with standard American keyboards in mind, so the symbol for multiplication is the asterisk (*) instead of × or · symbols used more in math. Likewise we use the / symbol for division instead of the ÷ symbol. The symbols were picked to make them easier to type when writing code.

Notice that exponents are done with two asterisks **. A

fairly common mistake is to use the caret symbol ^ instead. This could

have been used, but actually means something else in Python4.

Python follows the standard mathematical rules of precedence which can be overridden with parenthesis.

3.9 Example: Tips

As an example of working with numbers, let’s write a program that can figure the amount that you should tip a server at a restaurant. When the bill comes at a restaurant, it’s expected that diners will give a tip between 15 and 20 percent of the price of the meal. This can sometimes be tricky to figure out5, so let’s write a program to figure it out for us!

The program should start off by asking the user how much their meal

cost. To do that, we will need to use input combined with

the float function to read in a number that may have a

fractional part:

cost = float(input("How much was the bill? "))Next, we need to do a little math. If the user wants to give a 15% tip, then we should multiply the amount by 1.15. This will give a new number which is equal to the original amount, but is 15% more. We should save this number into a new variable:

total = cost * 1.15One mistake beginning programmers sometimes make is to not put the answer to something like this in a variable. For instance they might write a line like this:

# wrong

cost * 1.15This line of code doesn’t really do anything. It multiplies cost by 1.15, but it doesn’t save the answer anywhere. In order to make use of a result like this, we have to put it into a variable.

Now that we have the amount with a tip added in, we can print it for the user:

print("The amount with tip is", total)This will print out the full amount with tip added in, which we have just calculated. The whole program with comments added is below:

Program 3.5

# read in the starting cost

cost = float(input("How much was the bill? "))

# figure out the cost with a 15% tip added

total = cost * 1.15

# print the result

print("The amount with 15% tip is", total)Below is an example of running this program:

How much was the bill? 32.40

The amount with 15% tip is 37.26This program would be quite helpful in figuring out how much to tip a

server, but we can make it even better. What if someone wants to tip 20%

instead? We could of course just change the 1.15 in the

program to 1.20 instead.

But it would be even better if we asked the user how much they want to tip and then use that amount instead of a pre-determined amount.

So to start let’s ask them two questions instead of just one:

# read in the starting cost and tip amount

cost = float(input("How much was the bill? "))

percentage = int(input("How much do you want to tip? "))Now we have two variables. The first one, cost, will

store the cost of the meal before tipping. The second one,

percentage, will store the percentage the user wants to

tip.

Now we need to do a little bit of math. The first thing we need to do is to divide the percentage they entered by 100. That way we can go from 15 to the .15 that we need. The word “percent” actually means divided by 100.

Next we need to add 1 to this number. That way we go from the .15 to the 1.15 we used in the first program. Except now it will work with any percentage.

Then we can multiply that number by the cost of the meal. Altogether, that gives us this line of code:

total = cost * (1 + percentage/100) Notice that we used parenthesis to make sure to do the addition before the multiplication. The new and improved version of the program is below:

Program 3.6

# read in the starting cost and tip amount

cost = float(input("How much was the bill? "))

percentage = int(input("How much do you want to tip? "))

# figure out the cost with the tip added in

total = cost * (1 + percentage/100)

# print the result

print("The amount with tip is", total)And here is an example of running it:

How much was the bill? 41.40

How much do you want to tip? 20

The amount with tip is 49.683.10 Rounding

One last thing before we close out this chapter. I sort of carefully chose the inputs to the last program so that the output looked right. If we had picked other things, it would not look as nice. For example:

How much was the bill? 37.21

How much do you want to tip? 17

The amount with tip is 43.5357That just looks weird when we’re talking about money. We always round money to the nearest cent. We would not expect to see something like this, so let’s talk about how to fix it.

The best way is to round the result to 2 decimal places. This is done

with the round function, which takes the number we want to

round and how many decimal places to round to. We can try this in the

shell

>>> round(43.5357, 2)

43.54round always rounds to the nearest place. For

instance round(4.7, 0) rounds up to 5, while

round(4.3, 0) will round down to 4.

The program with this fix in place would look like this:

Program 3.7

# read in the starting cost and tip amount

cost = float(input("How much was the bill? "))

percentage = int(input("How much do you want to tip? "))

# figure out the cost with the tip added in

total = cost * (1 + percentage/100)

# round the answer to 2 decimal places

rounded = round(total, 2)

# print the result

print("The amount with tip is", rounded)This is a pretty advanced program! It takes two pieces of input, uses four variables, and does some sort of tricky math. It even makes sure that the output looks like the user would expect. Even better it actually solves a real-life problem most of us can appreciate. If you followed what we’ve done here, then great job!

3.11 Comprehension Questions

- Why is it important to understand the type of data stored in a variable in Python?

- What is the difference between an integer and floating point number? When would you use one versus the other?

- What does the + operator do with numbers and what does it do with strings?

- What number gives us the first character in a string when used as an index?

- What must we do with a number value read in with

inputbefore storing it in a variable?

3.12 Programming Exercises

Write a program to read in the length and width of a rectangle and print both the area and perimeter of the rectangle to the user.

Write a program to convert from feet to meters. There are 3.28084 feet in one meter. First read in the number of feet, do the calculation to find how many meters that is, and then print the result.

Write a program to read in the user’s first name and last name, and print out their initials. For example, if the user puts in “Margaret” and “Jones” it should print out “M.J.”

Write a program to print the average of 4 numbers that the user gives. You should read in the 4 numbers, compute the average, and then print the answer.

Imagine a snack bar that sells four different types of snacks: candy bars cost $1.00, bags of popcorn cost $.25, cans of soda cost $.75 and bottles of water cost $.50. Write a program to ask the user how many of each of these snacks they bought and tell them the total price of their order.

Chapter Summary

- A type is something associated with a variable that determines what things make sense to do with it.

- The string type is for storing text. Strings can be joined together, and you can get the individual characters out of them.

- There are two types of numbers in Python. Integers are for numbers which can’t have a fractional part, and floats are numbers which can.

- The

inputfunction gives us strings by default. We can read in numbers by using theintorfloatfunction. - Both types of numbers let us use math operators on them, to perform calculations.

- The

roundfunction is used to round numbers in Python.

Footnotes

Sometimes computer scientists come up with fancy words like this for very simple concepts. This is just one of many examples.↩︎

Of course, a computer has a set amount of memory, and a big enough number could in theory need more memory than you have, but that isn’t really an issue in practice.↩︎

These numbers are called “floats” because they have a “floating” decimal point. That means the decimal can appear in any position, for example 10.0, 1.0, 0.1, and .01 are all valid numbers. Some languages (not Python) also have fixed point numbers, where the decimal can’t move.↩︎

The

^is used for an operation called XOR, which is used for dealing with binary numbers.↩︎Especially if the meal included a few drinks.↩︎