Push Down Automata

Overview

Finite automata and regular expressions are equivalent. Any language generated by a regex has an equivalent DFA.

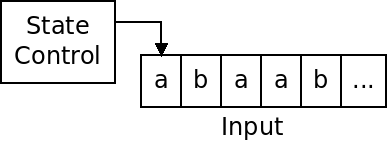

A DFA, as pictured below, has an input, and a state control:

Similarly, push down automata are equivalent to context free-grammars.

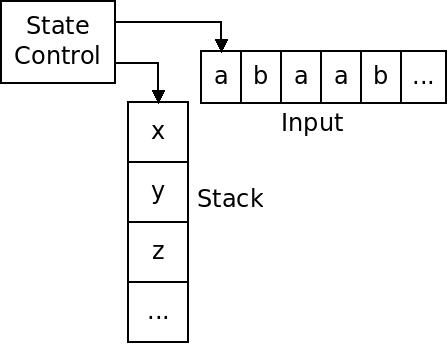

A PDA is an automata that has a finite number of states, but an unlimited stack to store symbols on:

The PDA can push items onto the stack, and pop items off, but cannot access any item but the top.

Formal Definition

A push-down automata consists of the following six things:

- $Q$ is the set of states.

- $\Sigma$ is the input alphabet.

- $\Gamma$ is the stack alphabet.

- $\delta: Q \times \Sigma_{\epsilon} \times \Gamma_{\epsilon} \rightarrow \mathcal P(Q \times \Gamma_{\epsilon})$ is the transition function.

- $q_0 \in Q$ is the start state.

- $F \subseteq Q$ is the set of accept states.

The notation $\Sigma_{\epsilon}$ means the union of input alphabet with $\epsilon$.

The difference from a DFA is the presence of the stack. At each transition, we can pop an item off the stack and/or push an item onto the stack.

Note that the transition function uses a power set, making PDAs non-deterministic.

Example: $\{0^n1^n \ |\ n \ge 0\}$

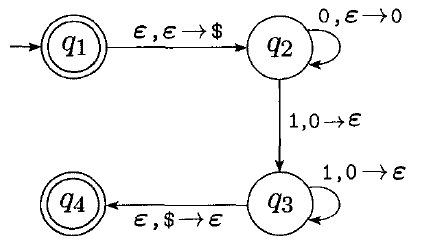

The following PDA accepts strings belonging to this language:

The transitions now include stack operations.

A transition of the form $X, Y \rightarrow Z$ means that we read $X$ as the next input symbol, pop $Y$ from the stack, and push $Z$ onto the stack.

If we omit a push or a pop, we use $\epsilon$.

Example: Palindromes

How could we design a PDA which accepts the language $\{w \ |\ w \text{ is a palindrome}\}$, where the alphabet is $\{a, b, c\}$?

Equivalence of PDAs with CFGs

We have said that a PDA is equivalent to a CFG. To show this, we need to show two things:

- Any CFG has an equivalent PDA that accepts the language it generates.

- Any PDA has an equivalent CFG, that generates the language it accepts.

CFG $\rightarrow$ PDA Conversion

If we have some context-free grammar $G$, we can construct a PDA $P$ that simulates a derivation using the grammar $G$.

$P$ starts by writing the start variable of $G$ on its stack. $P$ then applies the productions of $G$, matching input, and replacing variables on its stack.

$P$ must maintain the intermediate strings through the derivation, which contain variables and terminals.

Often $P$ will have several choices of which production to apply. It uses non-determinism to do this.

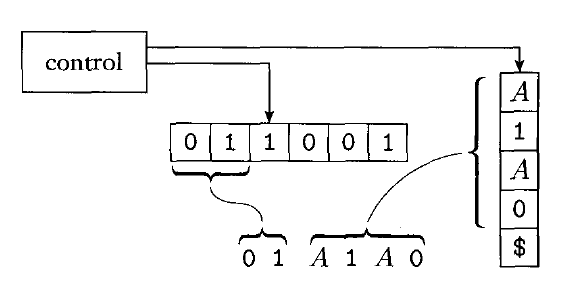

The stack of $P$ contains the intermediate string starting at the first variable. Any preceding terminals are matched against the input.

The following image shows how $P$ might look as it's deriving a string against some grammar:

Below is a description of the operation of $P$:

- Push the marker symbol '$' and the start variable onto the stack.

- Repeat the following steps forever:

- If the top of the stack contains a variable $A$, non-deterministically select a production of $A$, and substitute the right hand side of the production for $A$ on the stack.

- If the top of the stack contains a terminal symbol $a$, read the next input symbol. If it matches, repeat. If they do not, reject.

- If the stack symbol is '$', enter the accept state - which will accept if the input has been all read.

Example

Given the following grammar:

$S \rightarrow ASA \ |\ a$

$A \rightarrow a \ |\ b \ |\ c$

How would our PDA $P$ simulate the input "cab"?

How would our PDA $P$ simulate the input "abc"?

Can we draw the PDA $P$?

PDA $\rightarrow$ CFG Conversion

Any PDA also can be converted to a CFG. We will not go into this, however.

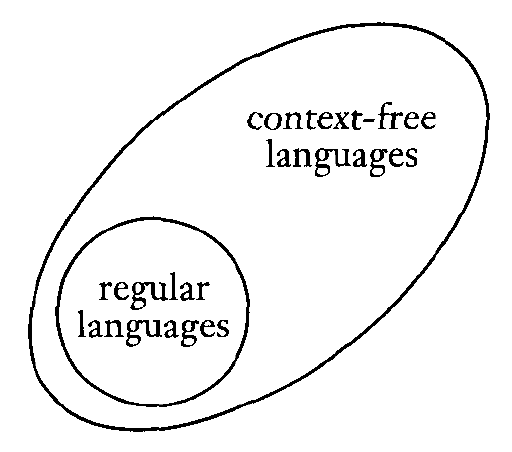

Regular and Context-Free Languages

According to the following reasoning, regular languages are a subset of context-free languages:

- Any regular language can be described by an NFA.

- Any NFA is also a PDA (one that just happens to ignore its stack).

- Any PDA defines a context-free language.

Below is a depiction of this situation:

This is a part of the "Chomsky Hierarchy" of languages. We will add to this throughout the semester.