Process Management

Overview

Today we will look at Linux processes and how to manage them. We will see how processes work internally as well as how to list them, search for specific processes, and suspend or kill them.

What is a Process?

A process is an instance of a program that is running on a computer system. A single

program, such as /usr/bin/ls for instance, is only stored as a program on

disk once. But it may be running as multiple separate processes at once, if multiple

users are running ls commands at the same time.

When a program is executed, the OS creates an address space for it (containing a global space, stack, and heap) and allocates some amount of memory to it. The process is then given CPU time to execute and access its memory. The OS ensures that each process can only access its own memory.

Each process contains the following properties:

- Process id (PID): a unique number that is assigned to each process when it was created. These are used to specify processes by commands and system calls.

- Parent process id (PPID): the PID of the process which created this process. Typically the init system (such as systemd) is the first process spawned and is the parent of all services, such as SSH. When you login over SSH, it creates a shell process for you and then commands you run are created by the shell. If a process dies while it still has children processes, the children are adopted by PID 1 (init).

- Owner (UID): The user who the process is running as. Typically inherited from parent process. The process is only allowed to access files that the owner is allowed to access.

- Group (GID): The primary group of the user running the process. Principally used for the default group when creating files.

- State: Whether the process is actively running, ready to run, etc.

- Niceness: The priority of the process, which is used for CPU scheduling.

- Open files: Which files the process has opened for reading or writing.

Listing Processes

The ps command can be used to list running processes. By default it shows

only processes that are children of the current session:

$ ps

PID TTY TIME CMD

39446 pts/2 00:00:00 bash

39793 pts/2 00:00:00 ps

We can search for all processes of a specific user with the -u flag:

$ ps -u ifinlay

PID TTY TIME CMD

399230 ? 00:00:00 systemd

399233 ? 00:00:00 (sd-pam)

399256 ? 00:00:10 sshd-session

399257 pts/0 00:00:00 bash

399285 pts/0 00:00:02 vim

400305 ? 00:00:00 sshd-session

400306 pts/1 00:00:00 bash

400323 pts/1 00:00:00 ps

We can also search for all processes using the -aux flags.

The a flag includes all processes (not just ours), the u

flag gives "user-oriented" fields such as state and CPU usage and the x

flag includes processes not attached to a terminal (such as daemons).

$ ps -aux 1 USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND 2 root 1 0.0 0.0 24396 15364 ? Ss Feb02 0:05 /sbin/init 3 root 2 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S Feb02 0:00 [kthreadd] 4 root 3 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? S Feb02 0:00 [pool_workqueue_release] 5 root 4 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? I< Feb02 0:00 [kworker/R-kvfree_rcu_reclaim] 6 root 5 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? I< Feb02 0:00 [kworker/R-rcu_gp] 7 root 6 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? I< Feb02 0:00 [kworker/R-sync_wq] 8 root 7 0.0 0.0 0 0 ? I< Feb02 0:00 [kworker/R-slub_flushwq] ...

On BSD-style unix, the hyphen before flags is optional and the ps command

supports that. So some people just give this command as ps aux.

We can also use the -o flag to look for specific process properties:

$ ps -o pid,ppid,cmd

PID PPID CMD

37541 37527 /bin/bash

40107 37541 ps -o pid,ppid,cmd

Another command which can be used to get info on processes is pidof which

simply tells us the PID(s) of any processes a given command is running:

$ pidof bash 37602 37541 35641

Which can be helpful for quickly finding the PID of a process you want to send a signal to.

Dynamic Process Info

The ps command gives you info on running processes at the time

you run the commands, but of course does not update that info as time passes.

The top command gives a dynamic process list that updates

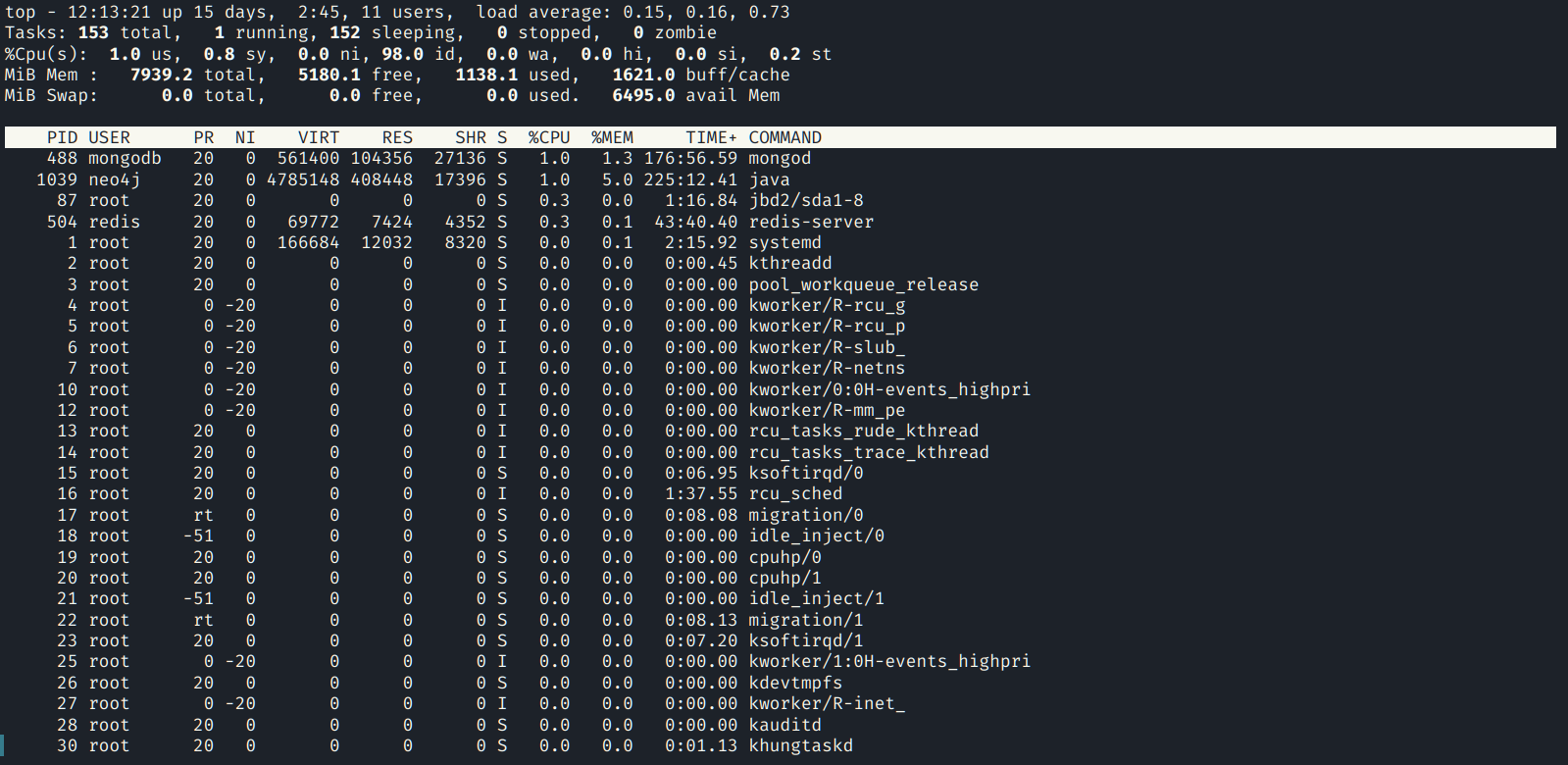

every few seconds. The program looks like the following:

The process list will be updated with time and is sorted by CPU usage. If a system is lagging this makes it easy to see what is taking the most CPU time. You can quit out of top by hitting the 'q' key.

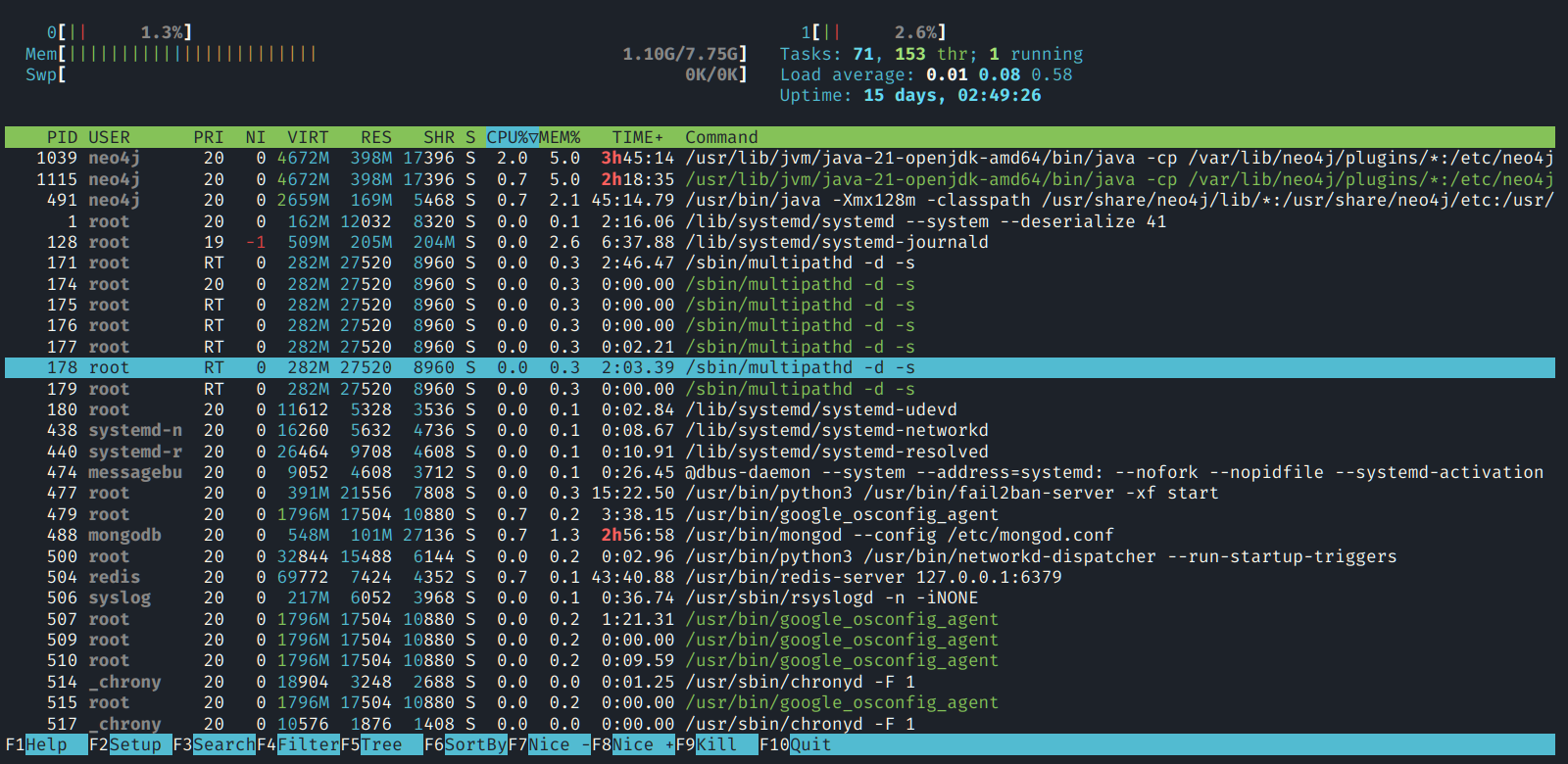

There is also a more powerful version of top called htop,

which may need to be installed before it can be used. This program

is more interactive and colorful than top:

With htop, you can use the search for processes, change the sort criteria, change process priority and send signals directly from this program.

Process Life Cycle

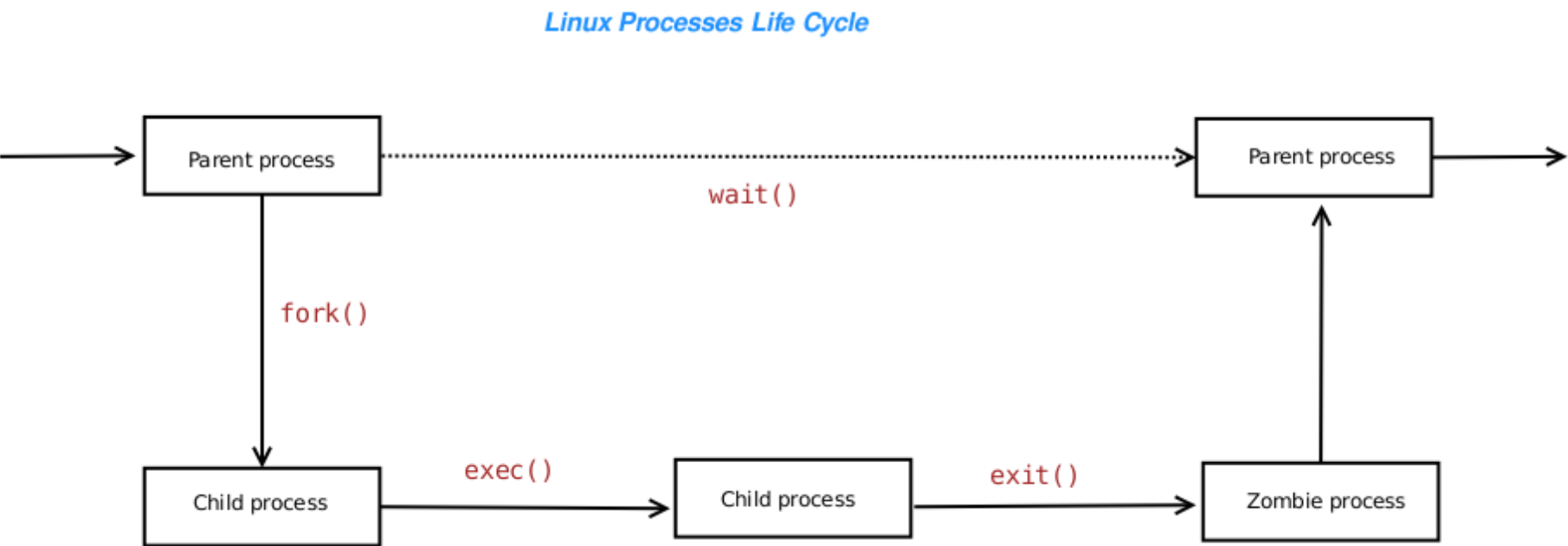

Below is a diagram of the typical way processes are created and destroyed, for instance when running shell commands:

Every process (except for init) is created by its parent. This is done

with a system call named fork (because the execution creates

a "fork in the road" with the parent and child continuing on separately).

The child then typically invokes a system call named exec

to begin running a program from disk.

While the child is running, the parent process is waiting for the child

to finish. When the child does (by calling the exit system call,

control is returned to the parent. A "zombie" process is a process which has

finished execution, but still has an entry in the process table. This state

of affairs normally only lasts for milliseconds before the entry is removed.

While a process is executing, it can be placed in one of a variety of states. When a process is first created it is admitted into the "ready" state which means it can be executed, but isn't currently running. The OS scheduler can then move it to the "running" state where it is actively being run on the CPU. It can be interrupted and sent back to the "ready" state by the scheduler. It may need to wait for an I/O request (such as reading user input or a file) in which case it is in the "waiting" state. Finally when it exits, it is in the "terminated" state briefly before being removed.

Changing Niceness

The Linux concept of process priority is called "niceness". The more nice a process is, the more willingly it will give CPU time to other processes (and thus the lower its effective priority). Niceness is represented with an integer from -20 (highest) to 19 (lowest).

We can change the niceness value with the renice command:

$ renice -n 10 -p PID

Where "PID" is replaced with the process id of the process we wish to modify the niceness value for. We can only make our processes more nice as a regular user. Only root can make processes less, that is higher priority.

The default level of niceness is usually 0 with processes inheriting their

niceness from their parent process. We can check current niceness values

with ps:

$ ps -ax -o pid,ni,cmd

Setuid and Setgid

Normally when a program is launched by a user, the UID of the process

matches that of the user. For example, wen you run the cp

command, the process gets your UID and GID. This prevents that process

from accessing things your user is not allowed to access (such as copying a

file you don't have read permission for, or writing to a directory you

don't have write permission for.

However, some programs have either the setuid or setgid

permission bits set for them. This means that they run with the effective UID/GID

of the owner of the executable and not the user who runs them.

An example of this is the passwd command. When we run this as

a regular user, it needs to write our hashed password to the /etc/shadow

file, which normal users are not even allowed to look at. We can see that the

setuid bit is set in the ls output:

$ ls -l /usr/bin/passwd -rwsr-xr-x 1 root root 118168 Apr 19 2025 /usr/bin/passwd

There is an 's' instead of an 'x' in the user execute permission field

which indicates that the setuid bit is on. When this executable is executed

by any user, the effective UID of the resulting process is not our user's UID,

but the owner of the file (which in this case is root). That means this

process is allowed to do anything root can, such as write to /etc/passwd.

This is only done for very few programs which are carefully written and reviewed. We don't want to make exceptions to the permission rules unless we absolutely have to, such as in this case.

The setgid bit is the same, except for the group instead of user. An example

of a program with this bit set is crontab:

$ ls -l /usr/bin/crontab 52 -rwxr-sr-x 1 root crontab 51936 Jun 13 2025 /usr/bin/crontab

No matter who runs this program, it runs with the group crontab.

This program is for scheduling repeated tasks, and so anyone in that group

is allowed to schedule such tasks. This mechanism allows for that to take place.

These bits can be added to an executable with the chmod command,

but is not very common as there are security implications of running a process

as a different user/group especially when that user is root.

Signals

We can interact with processes by sending them signals, which are notifications sent to a process. Processes can catch signals and handle them in whatever way they want, although some signals cannot be caught (such as KILL and STOP).

Signals are sent with the kill command, despite the fact that

KILL is only one signal which we can send (and is not even the default). When

we don't specify which signal to send, it is actually TERM which is sent:

$ kill PID

Where PID is the process id of the process we wish to send the signal to. We can also specify the signal to send using either the four-letter name, or the integer code for the signal. So the following two commands are both equivalent to the one above:

$ kill -TERM PID $ kill -15 PID

The TERM signal tells a process "please terminate". If the process does not catch this signal, it will be terminated. Some processes catch it to try to ensure a clean shut-down (such as saving files etc.). Generally one should try to send the TERM signal to a process we want to end. However, if it does not cause the process to stop, we can send the KILL signal instead:

$ kill -KILL PID $ kill -9 PID

This signal cannot be caught and will always cause the process to be stopped. Of course we are only allowed to send signals to our own processes. Only the root user can send signals to processes of other users.

There are two "user" signals supported by Linux: USR1 and USR2. These

can be caught by applications to do application-specific things. For example,

the MySQL database server catches USR1 and flushes the log files if it receives it.

The dd command which copies block data prints a status message

when t receives USR1.

These user signals can be sent the normal way:

$ kill -USR1 PID $ kill -USR2 PID

We can also send signals with the killall command

which sends signals to processes by command instead of PID. For instance,

we could send TERM to all apache2 processes using the following command:

$ killall apache2

This is equivalent to the following:

$ kill $(pidof apache2)