The Linux Operating System

Overview

Linux is an operating system which was first released by Linus Torvalds in 1991. His initial goal was to make a freely available operating system kernel based on Unix. It has been continuously developed since then and is now used on the vast majority of servers and super-computers (as well as phones, tablets, laptops and desktops).

Technically "Linux" refers to the kernel of the operating system only, which is the part which manages hardware resources and allows user-space applications to run. An operating system also needs various applications to be complete (such as a shell, compiler, utility programs). Most of these are provided by GNU and so some people call Linux "GNU/Linux". But by and large most people refer to the whole package as just Linux.

Because Linux is just a kernel, which is usually paired with GNU user-space applications, it would be difficult to download and install it directly. Instead, there are various distributions of Linux which include the kernel, applications and an installer.

Distributions differ in terms of what versions of software they come with, how they are installed, and how they manage software packages. Popular distributions include:

Debian

Non-commercial distribution which is very stable. Many other distributions like Ubuntu, Linux Mint, and Pop OS are based off of it.

Fedora

Developed by the company Red Hat who also develop Red Hat Enterprise Linux, which is commercial. Fedora is the test bed for software that goes into RHEL. There are also free clones of RHEL such as CentOS and Alma Linux.

Gentoo

Focusses on compiling code from scratch. Rather than download pre-compiled packages, they are compiled on the user's machine.

Arch Linux

Focused on enthusiasts which installs a minimal system which is then built up by the user.

openSUSE

A non-commercial distribution from the German company SUSE, who also offers the SUSE Linux Enterprise.

In this class, we'll use Debian which is extremely reliable and completely free.

The Unix Philosophy comes from Unix and has survived in Linux, and

is to design software that does one job well, and composes with other software.

For instance, the program to list processes on Linux, ps does not

have functions for searching or sorting processes. Instead, one can combine

it with separate programs (grep and sort) to

accomplish that.

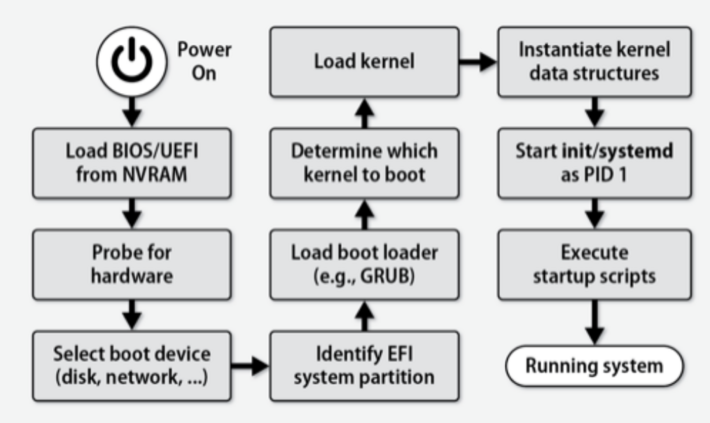

Booting

The above image depicts the Linux boot process. The first piece of software which runs when you turn on a computer is the UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface) which is firmware. Firmware is software which comes with hardware, not installed by the user. UEFI replaces the older BIOS system, though many still use the term "BIOS". The main job of UEFI is to locate the disk partition containing your operating system and begin booting it.

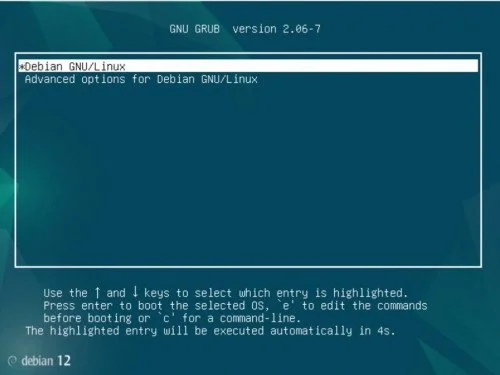

Next the bootloader runs, which is the first piece of software that does not come with the hardware. The most common Linux bootloader is grub (Grand Unified Boot Loader). The bootloader allows you to pick which Linux kernelto boot into (if you have multiple) and select boot options.

These boot options include things like whether to show boot messages and enabling or disabling of kernel modules at boot time. Also critically the boot target can be selected:

| Target | Meaning | Run-level |

|---|---|---|

| poweroff.target | Shutdown the computer | 0 |

| rescue.target | Root-only login with minimal OS services. Used for fixing problems that cannot be addressed normally. | 1 |

| multi-user.target | Multiple users and networking is enabled | 3 |

| graphical.target | Same as multi-user, except the graphical system (if installed) is launched | 5 |

| reboot.target | Reboot the computer | 6 |

With Google Cloud, much of this is normally hidden from us. However, you can drop down to rescue target if needed in Google Cloud by opening the serial console (instead of connecting over SSH) and then editing the grub menu.

Daemons and Initialization

After the bootloader begins booting the operating system, the kernel initializes

and launches the first process, which is the init system. This

is a process which is responsible for launching other needed services and systems.

The de facto standard init system in modern Linux is systemd.

Systemd is complex and does a lot of different things. It manages "units" which can include targets (such as the rescue and multi-user targets discussed above), sockets, devices, timers, mounted partitions and more.

The way we will interact with systemd most is to use it to manage which daemons are running on our system. A daemon is a process which is run continuously in the background. An example is the SSH daemon (sshd) which listens for incoming SSH connections. In mythology, daemons or daimons are spirits which maintain the order of things.

Systemd refers to daemons as "services" and they are controlled by .service files which can be located in several places:

- /usr/lib/systemd/system - where packages deposit unit files during installation

- /lib/systemd/system - alternate to the above location

- /etc/systemd/system - local unit files and customizations

- /run/systemd/system - scratch area for transient units

In addition to .service files, these directories contain files for the other types of units systemd manages such as .target, .timer, and .device files. The .service files define the properties of running daemons on the system.

Managing Services

Each unit file we have defines a unit which systemd can interact with. We

use the systemctl command to interact with daemons. There are

several sub-commands to systemctl that are useful.

We can see which units of different types are available:

$ systemctl list-units $ systemctl list-units --type=service

We can start and stop services

$ sudo systemctl start ssh $ sudo systemctl stop apache2.service

The ".service" extension is optional in these commands. Also listing services can be done as a regular user, but managing them must be done as root (hence sudo).

We can also enable or disable services with systemctl. If a service is enabled, it starts automatically when the machine reboots, if it is specified as needed by the run-level we boot into. For instance, SSH is specified as needed by the multi-user and graphical targets so if it is enabled it will start when we boot to those targets:

$ sudo systemctl enable ssh $ sudo systemctl disable apache2

We can check the status of a service:

$ systemctl status ssh

Systemd Logs

All systemd units share a centralized logging system. The journald

daemon manages these logs an can be interacted with using the journalctl

command. This command by itself will list the most recent messages from all units:

$ journalctl $ journalctl -f

Using the "-f" flag gives us a live feed where new messages are printed to the screen as they are logged. We can also specify one unit in particular to look at the logs for:

$ journalctl -u ssh

File System

The Linux file system begins with the / directory, which is the root of everything.

All other directories and files are descendants of the root. Below are some of the more

important file system locations:

/etc: System-wide configuration files/boot: Files used during the boot process (such as grub config files)/home: User home directories/usr/bin: User applications/usr/sbin: Applications generally used by root/usr/share: Application data files/dev: Device files/proc: A virtual directory that displays information on the system/root: The root user's home directory/tmp: Temporary files/var/log: Log files/var/www: Default location for website data

There are two ways to specify a path on the command line:

- Absolute paths begin with a / and start with the root

of the file system. They don't depend on where you currently are. For example

you can see a listing of the python3 executable with the following command:

$ ls -l /usr/bin/python3

This will work regardless of what your present working directory is. - Relative paths don't begin with a / and are relative to your present working directory. For instance, the following commands will accomplish the same thing as the above:

$ cd / $ ls -l usr/bin/python3 $ cd /usr $ ls -l bin/python3 $ cd /user/bin $ ls -l python3A relative path essentially resolves to the present working directory, followed by the relative path.

File Types

One of the precepts of the Unix philosophy is that "Everything is a File". Concepts that other operating systems have distinct objects or data structures for, Unix represents with regular files. Some examples of this:

- The files

/proc/cpuinfoand/proc/meminfohave information on the CPU and memory resources available to the system. These files don't actually exist in the normal sense, but the OS will provide them when they are opened. - The file

/dev/randomprovides random numbers when you read from it. Again, this is not an actual file, but the interface for accessing it is the same as if it was.

Linux has 7 types of files. Which type of file you have can be seen with the

first character of output of the ls -l command:

| Symbol | File type |

|---|---|

| - | Regular file |

| d | Directory |

| l | Link |

| c | Character device |

| b | Block device |

| p | Pipe |

| s | Socket |

By treating lots of different types of things as just files, Linux allows us to interact with different types of objects using the same interface.