Managing Processes

Processes

A process is an instance of a program that is currently running. Using the command line, nearly every command that you type launches a new process which runs until it finishes. When you run your own programs, those will run as processes as well.

Usually processes start, do their work, and finish without our having to worry about it, but sometimes we will want or need to intervene. This week we will look at how to see what processes are running, and interact with them.

Listing Processes

We can list the processes which are running on a system with the ps

command. With no options, ps will list the only the processes which

we have started in the current terminal ourselves:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 17371 pts/0 00:00:00 bash 17386 pts/0 00:00:00 ps

There is a line for each of the two processes which I have launched. The

first is "bash" which is the shell process. That is the program which

interprets our key presses as commands. The second is the ps command

itself. Because it is running at the time when it lists processes, it includes

itself in the output.

The output includes the following columns by default:

PID

The unique process identifier. This can be used to manage individual processes as we will see.

TTY

TTY stands for "TeleTYpewriter", an old term for a computer terminal which could send commands to a mainframe computer. Here, TTY refers to which terminal the process was launched under. The 'p' in "pts/0" stands for "pseudo" which indicates the terminal is a virtual one managed for us by the SSH server. You normally don't need to worry about the TTY, but if you have multiple SSH windows connected at once, the TTY indicates which one a process belongs to.

TIME

The amount of CPU time that the process has used. Neither

bashnorpsare CPU intensive, so they have used less than one second each of CPU time.CMD

The command which was used to initially launch the process.

By default ps just shows processes from our current session and

user. We can also view all processes running on a system by passing

ps the "-A" flag. Here is a small subset of the output when I ran it

(the full list had 96 processes):

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps -A

PID TTY TIME CMD

1 ? 00:00:01 systemd

2 ? 00:00:00 kthreadd

4 ? 00:00:00 kworker/0:0H

12030 ? 00:00:00 apache2

12194 ? 00:00:00 apache2

12203 ? 00:00:00 apache2

6586 pts/0 00:00:00 bash

6624 ? 00:00:00 sshd

6705 ? 00:00:00 sshd

6706 pts/1 00:00:00 bash

6711 pts/1 00:00:00 man

6893 pts/0 00:00:00 ps

The first process, with a PID of 1 is the "systemd" process which runs when the operating system first boots and is responsible for getting everything else going.

A few other processes you will see are "apache2" which is the web server running on cpsc.umw.edu. The "sshd" process is the SSH server. There are multiple of these server processes because they create a new process to handle each client connection.

I also have two terminals connected, one running man, and one running ps. This is why there is a pts/0 and pts/1.

Launching a Process in the Background

Normally, when we launch a process via the command line, it runs to

completion and we cannot interact with the shell until it finishes. For

instance, try running the sleep command which does nothing but

runs for the number of seconds given as its argument:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 3 ifinlay@cpsc:~$

This command produces no output, but runs for three seconds. Try running

this command and you will see that commands we enter take control of the shell

because, during the three seconds during which sleep is executing, we

are not able to use the command prompt. This is true for all of the other

commands we have discussed, but they generally run so quickly that it makes

no difference.

To run a command in the background, we can end it with the & character. This launches the process, except it returns control back to the shell immediately. In the following example, we run the sleep command in the background, and are able to execute commands immediately after:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 3 & [1] 3149 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 2982 pts/3 00:00:00 bash 3149 pts/3 00:00:00 sleep 3150 pts/3 00:00:00 ps ifinlay@cpsc:~$ [1] + done sleep 3 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 2982 pts/3 00:00:00 bash 3151 pts/3 00:00:00 ps ifinlay@cpsc:~$

After running sleep in the background, I immediately ran the ps

command which shows that sleep is currently running. After the three seconds have

elapsed, the shell gives the message "[1] + done sleep 3" informing me that

sleep has finished executing. Also notice that the shell gives us the

process ID for the sleep command as it launches it.

Running the sleep command in the background is not terribly useful, but starting long-running commands in the background (such as copy commands of large amounts of data) is useful. It's also useful when writing our own server-style programs, where the program runs in the background and we interact with it some other way.

Cancelling A Process

To cancel a process that is currently running (not in the background), you can use the Control-C shortcut. For example, we can cancel a sleep command:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 100 ^C ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 17453 pts/3 00:00:00 bash 17471 pts/3 00:00:00 ps

As you can see, this ends the process. This is helpful when writing our own programs. If we have an infinite loop, killing the program like this is the only way to stop it!

Suspending a Process

We can also suspend a process that is running with the Control-Z shortcut. This does not kill the process, but pauses it, returning control to your shell:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 100 ^Z [1]+ Stopped sleep 100 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 17680 pts/3 00:00:00 bash 17683 pts/3 00:00:00 sleep 17686 pts/3 00:00:00 ps

As you can see, in this case, the sleep command is still in the process list.

However, as a suspended process it does not actually continue to execute, it is "paused".

We can see a list of all suspended processes with the jobs command:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ jobs [1] + suspended sleep 100

Resuming a Process

To resume the process that was most recently suspended, use the fg command.

The process I most often suspend is Vim. For example, I might suspend Vim, check a man

page and then resume Vim using fg. This might look like this:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ vim program.c bash: suspended vim program.c ifinlay@cpsc:~$ man sleep ifinlay@cpsc:~$ fg

Here I used Control-Z to suspend Vim, ran some other command(s), and then went back to Vim with the fg command.

If there are multiple suspended commands, you can select the one you wish to

resume by passing the number assigned to it in the output of jobs with a

percentage sign:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ jobs [1] suspended vim a.txt [2] - suspended vim b.txt [3] + suspended vim c.txt

Here, there are three Vim processes which have all been suspended. To resume the first one we would use:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ fg %1

Likewise, passing "%2" or "%3" would resume the second and third processes

listed in the output of jobs, respectively.

We can also resume a process with the bg command. The difference

between fg and bg is that fg resumes the command in

the foreground - as if the process was launched normally - while bg

resumes the process but in the background - as if the process was launched with

an & at the end.

Resuming a process like Vim in the background makes little sense, but we can

use Control-Z and bg to send a process to the background after it was

initially launched in the foreground, which can be useful. For instance,

sometimes I will run a program, and realize that it is taking a long time.

Instead of waiting, we can suspend it, then run it in the background with

bg, and then carry on with other tasks instead of waiting

around.

Sending Signals

We can also interact with running processes by sending them signals. A signal is a message that is passed to a running process, telling it to do something. When we cancel a process with Control-C, we are actually sending it the "SIGINT" signal (which stands for "signal interrupt"). Likewise, hitting Control-Z sends the process the "SIGTSTP" (which stands for "signal stop").

We can send these, and other, signals to a process with the

kill command. It is named "kill" because the default behavior of

kill is to send the "SIGTERM" signal which terminates, or kills, a

process. But despite its name, it can be used to send other signals that don't

kill a process. kill takes the process id of the process to which

it will send a signal.

The example below shows how kill can be used to terminate a process which

is running in the background:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 100 & [1] 18167 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 17792 pts/1 00:00:00 bash 18167 pts/1 00:00:00 sleep 18168 pts/1 00:00:00 ps ifinlay@cpsc:~$ kill 18167 [1] + terminated sleep 100 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 17792 pts/1 00:00:00 bash 18175 pts/1 00:00:00 ps

The process id (18167 in this case) can be seen in the output of ps.

In this case we killed the sleep process that was running in the background with

the default SIGTERM signal sent by kill.

Sometimes processes do not respond to the SIGTERM signal. Processes are able to catch it and handle it in a graceful way if they can. In some cases, processes do not terminate even when given the signal to. In these cases, we can use the more extreme "SIGKILL" signal which kills processes without giving them a chance to respond.

This is done by passing the "-KILL" option, or as is more common, by passing the "-9" option:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 100 & [1] 18196 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 17792 pts/1 00:00:00 bash 18196 pts/1 00:00:00 sleep 18197 pts/1 00:00:00 ps ifinlay@cpsc:~$ kill -9 18196 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ [1] + killed sleep 100

Note: So to recap, we send signals with the "kill" command which sends the "SIGTERM" signal by default. It can also be used to send "SIGKILL". It's kind of strange that the command to send signals is named after just one of the commands it can send, and not even the default one.

kill which sends SIGTERM and kill -KILL or

kill -9 which send SIGKILL are the most commonly sent

signals, but there are other signals which kill is able to send.

For example, "SIGUSR1" is ignored by most commands, but a few use it for some

special purpose. For example, dd (a command for copying files and

disk drives), prints its progress when sent the USR1 signal. This is helpful

to check the status of a long-running copy:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sudo dd if=/dev/sda of=/dev/sdb bs=4096 & [1] 32823 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 31668 pts/2 00:00:00 bash 32823 pts/2 00:00:00 dd 32825 pts/2 00:00:00 ps ifinlay@cpsc:~$ kill -USR1 32823 # dd if=/dev/sda of=/dev/sdb bs=4096 count=1048576 335822+0 records in 335821+0 records out 343880704 bytes (344 MB, 328 MiB) copied, 6.85661 s, 50.2 MB/s

Sending Signals to Multiple Processes

The killall command can send signals to processes. killall

works very similarly to kill except that instead of passing the process id as

an argument, we pass the name of the command to send the signal to. killall

will send the signal to all processes with that name.

For example, the following shows how we could send the SIGTERM signal to all sleep processes:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 100 & [1] 1482 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 101 & [2] 1483 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ sleep 102 & [3] 1484 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 1472 pts/2 00:00:00 bash 1482 pts/2 00:00:00 sleep 1483 pts/2 00:00:00 sleep 1484 pts/2 00:00:00 sleep 1485 pts/2 00:00:00 ps ifinlay@cpsc:~$ killall sleep [1] terminated sleep 100 [2] - terminated sleep 101 [3] + terminated sleep 102 ifinlay@cpsc:~$ ps PID TTY TIME CMD 1472 pts/2 00:00:00 bash 1488 pts/2 00:00:00 ps

Here, killall sent the SIGTERM signal to all of the processes with the command

name "sleep" which causes them to exit all at once. This command can be used to send signals

to processes by name instead of PID, even if there's only one. killall can also

take the signal we wish to send. For instance, to send the SIGKILL signal to all processes

called "myprog", we could use:

ifinlay@cpsc:~$ killall -KILL myprog

Viewing Process Activity

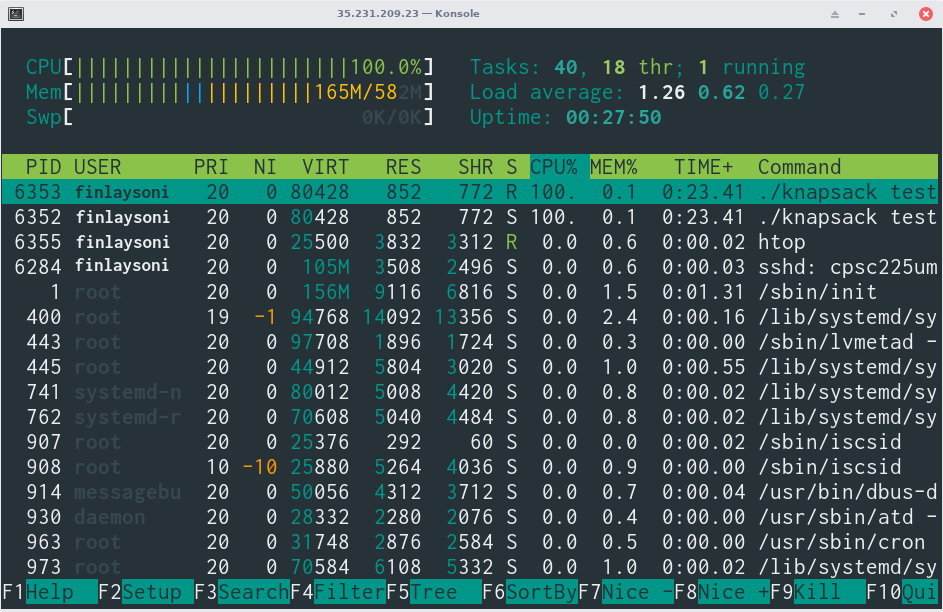

The htop command can be used to view dynamic process activity. It

displays which processes are currently using the CPU and memory of the machine.

htop updates the display every second until you exit the program by

pressing the 'q' key. Below is a screen shot of htop:

The output of htop.

Here, I am running a CPU-intensive program called "knapsack" which is using 2 processes taking 100% CPU each. You can also see htop itself, and some system processes running.

htop is helpful for finding which processes are taking up system

resources. The process ids are also listed in the first column.

You can use the arrow keys to scroll through the processes. As you can see

on the bottom of the screen, you can use F9 to Kill a process. That brings up

a menu asking you which signal you wish to send to the chosen process.

htop is a convenient way to find and kill rogue processes.